A Short History of New York City’s Emergency Ambulance Services

By Mark Peck, EMT-P, James Martin, EMT-P, Brian J Maguire, Dr.PH, MSA, EMT-P

Original Article from Jems.com | Posted December 1, 2022

A "Bread Box" 1972 Grumman. (Photo Used by Permission/New York City Fire Department EMS Museum)

Although the emergency medical services (EMS) profession can trace its ancestry to ancient Greece,1 the first municipal ambulance service in the U.S. was established in 1869 at Bellevue Hospital in New York City (NYC).2 The purpose of this paper is to provide a short overview of what is known about the provision of ambulance services in NYC. Although some of the history of the NYC EMS system is documented, and is cited here, much of what is described here, especially about the early days, has been collected over the past 50 years, from many sources, due to the personal interests and dedication of the first two authors.

Credit for the first Bellevue ambulance goes to Dr. Edward B. Dalton, who had designed an effective system of removing injured soldiers from the battlefield during the Civil War.3Recognizing that the wounded were sustaining significant additional injuries in the wagons being used to transport them, Dr. Dalton added roofs for shelter, a suspension system to cushion the ride and a red cross for identification. The Dalton ambulance became the standard for the military ambulance and the lessons he learned on the battlefield he brought to NYC when he returned to Bellevue Hospital after the war.3

Birth of EMS: The History of the Paramedic

The first horse-drawn ambulances were staffed by a driver and an intern; the intern was typically fresh out of medical school. Specifications for ambulance equipment stated: “Each ambulance shall have a box beneath the driver’s seat, containing a quart flask of brandy, two tourniquets, a half-dozen bandages, a half-dozen small sponges, some splint material, pieces of old blankets for padding, strips of various lengths with buckles, and a two-ounce vial of persulphate of iron.”2 During the first year, Bellevue Hospital fielded two ambulances. That year over 1,400 calls for help were answered.3 Due to this success, five more ambulances were added the following year.

A horse-drawn ambulance from Bellevue Hospital, 1886. (Public Domain)

While the system grew rapidly over the next few decades, incorporating ambulances from additional hospitals, the staffing model remained unchanged for about 70 years. Each hospital ran its own ambulance service, typically staffed by a physician and driver, with dispatching duties handled by the police department.

Barely four feet wide, early ambulance wagons were open to the elements and relied on a foot-pedal operated bell to warn of their approach. With only a cabinet under the driver’s bench, little equipment was carried. In fact, there was no equipment designed for prehospital use, no portable oxygen, suction or immobilization equipment. Rudimentary medical supplies were carried in the doctor’s bag and most patients were treated and left at home to recover. Patients requiring transport to the hospital were moved using a military style stretcher consisting of a leather pad stretched between two poles.4

The neighboring City of Brooklyn across the East River took note of the success of the ambulance service in New York City (then only Manhattan and the Bronx) and began plans to create their own service in 1873. The first proposal called for two horse drawn ambulances to cover the city’s 70 square miles of land; each staffed with a surgeon and a driver.5 A petition to begin the service noted that Brooklyn had a system in place to care for a horse injured on a city street but no system to care for a person injured on the same street.5

The Origins of EMS in Military Medicine

The consolidation of Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island into the City of New York in 1898 resulted in massive changes to most municipal services such as police and the fire department. Coordination and regulation of ambulances services initially remained with the police department, while the ambulances were owned and staffed by Bellevue and Allied Hospitals in Manhattan and the Bronx, and the Department of Public Charities – later called the Department of Public Welfare – in other boroughs. Many of the “voluntary” hospitals in New York City were also providing ambulances in their service areas under this system (“voluntary” refers to a private nonprofit hospital).

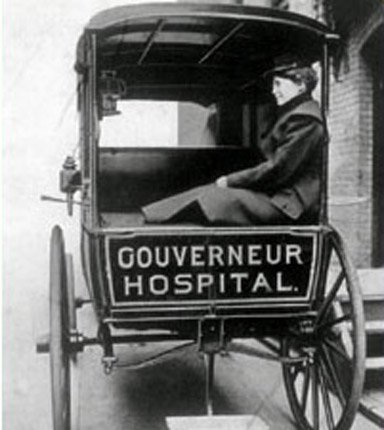

During the first three decades of NYC ambulance history, the “ambulance surgeons” were all men, as the work involved breaking up barroom fights and walking up several flights of tenement stairs lit only by their portable kerosene lanterns. But in 1903, Dr. Emily Dunning successfully challenged the patriarchal system to become the first woman ambulance surgeon.6

Dr. Emily Dunning (Public Domain)

The next major system improvement came in 1908 with the arrival of the first motorized ambulances. Three propulsion systems competed for the city’s business: Steam, electric and gasoline, with the latter proving the most reliable and winning the contract. The last horse-drawn ambulance was finally retired in 1922.3

Through the early 1900s, New York City’s population grew rapidly and with it came a significant increase in demand for ambulance services. By 1929, when the Department of Hospitals was created to unify the city’s municipal hospital system, there were 45 hospital-based ambulances (12 municipal and 33 voluntary) and an annual call volume of 343,000. Each hospital had its own rules, and patients were usually brought back to that ambulance’s hospital, even if a closer hospital was by-passed. By the late 1930s, NYC ambulances were all built on truck chassis and the drivers were solely responsible for the operation and maintenance of their vehicles.

At the outset of World War II, the system took a significant step backwards as a vast number of doctors and nurses were called into active military service, leaving a void on the ambulance. To fill the doctor’s vacancies, nurses’ aides and orderlies were (often reluctantly) assigned to ambulance duties, much to the chagrin of the public, who were used to medical professionals responding.

Doctors did return to ambulance roles after the war, but only on “special call,” such as obstetric assignments and entrapments requiring field amputations. But the vast majority of calls were handled by “ambulance attendants;” these personnel had the equivalent of first aid training no more extensive than what was taught to Boy Scouts. The first radio-equipped ambulances appeared in 1952.7

Photo Used by Permission/New York City Fire Department EMS Museum

In the 1960s, the Department of Hospitals, Ambulance and Transport Division established a more unified ambulance service, and standardized training and equipment. Annual call volume was now approaching 400,000.

The 911 System was created in 1968 linking NYPD and EMS communications. Ambulances were dispatched from the police communications center at 240 Centre Street. The following year, the Department of Hospitals was replaced by the Health and Hospitals Corporation, a quasi-municipal agency responsible for managing 16 city hospitals, three extended care facilities and the ambulance and transportation service (which became NYC*EMS the following year). The NYC*EMS agency had 16 municipal ambulance stations scattered throughout the city, most attached to city hospitals.

In 1969, the NYC EMS system consisted of 109 ambulances; 60 were city ambulances and 49 were provided by the voluntary hospitals. The same year the city used computer simulation for the first time to determine the optimum location for those ambulances.8

In April 1972, NYPD relinquished ambulance dispatching to NYC*EMS, which established an independent EMS Communications Center at 377 Broadway in Manhattan. Assignments were taken by call receiving operators and written on cards that moved by belts to the borough dispatch radio positions in the next room. The majority of dispatch radio traffic was limited to one shared frequency for Manhattan and the Bronx, and a second frequency for Brooklyn and Queens. Staten Island ambulances remained on the old NYPD Staten Island frequency, competing with police assignments for airtime. These congested frequencies often led to delays and the need to repeat transmissions.

The Story of ‘Emergency!’ Never Gets Old

Federal regulations mandating the new national Emergency Medical Technician qualification as minimum requirements for ambulance staff were established in 1970 and training NYC’s ambulance technicians began immediately. The program was soon expanded to cross-train the motor vehicle operators and ambulance technicians in both ambulance operation and patient care. A new title was created: “ambulance corpsman.”

At about the same time, NYC, in collaboration with Albert Einstein College of Medicine, secured a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation to establish a pilot paramedic training program. The initial group of advanced life support (ALS) providers hit the streets of the Bronx in July of 1974 in two new paramedic units. This major advancement effectively brought the hospital’s emergency room capabilities to the patient for the first time. The paramedics only covered half the county and only for two eight-hour tours. It would be another three years before the training program would be expanded to provide sufficient personnel to staff ALS units in other boroughs.

Then the NYC Medical Advisory Committee (MAC) was established, comprised of the emergency department physician directors from all the city and voluntary hospitals running 911 paramedic ambulances. The MAC established a fixed set of ALS protocols covering medications and therapies available to paramedics. Unlike the Los Angeles County Fire Department program, which introduced the paramedic concept to the nation through the popular TV program Emergency, the majority of ALS care in NYC was authorized in standing written orders, with physician radio contact minimized to essential decision points. Annual call volume was now 600,000.

A 1942 Cadillac belonging to Morrisania Hospital, Bronx, NY. (Photo Used by Permission/New York City Fire Department EMS Museum)

In the mid-70s, having outgrown the Broadway facility, NYC*EMS moved into its new headquarters in Maspeth, Queens. There they created a state-of-the-art computerized communications center. With these improvements came radical changes in communications. A computer aided dispatch system was integrated into the 911 framework. Statistical analyses of response times allowed for strategic deployment of ambulances and dynamic scheduling. Old style step-van style ambulances, in use since the 1960s, were replaced with Type 1 modular vehicles. Amenities such as on-board oxygen and suction, as well as improved cabinetry were added. For the first time, NYC*EMS supervisors began to patrol and respond to calls with crews. Portable radios were issued to ambulance crews to facilitate communications with dispatchers and supervisors. Training in mass casualty incident management began as did exercises such as multi-agency airport crash drills.

By the early 80s, the NYC*EMS agency was one of the approximately 70 independent agencies providing ambulance services as part of the NYC EMS System. The other agencies included about 13 hospital-based ambulance services, about 40 volunteer ambulance services, private ambulance services, and ambulances operated by other agencies primarily for use by their members or employees. The NYC*EMS ambulances, along with ambulances operated by the voluntary hospitals, collectively responded to all the 911 EMS calls in the city.

In 1980, NYC*EMS established its one-week emergency vehicle operators’ course; the program was offered to incumbents and then to all incoming personnel. In 1981, the first NYC*EMS supervisor’s course was taught at the EMS Academy, the Academy began coordinating basic and refresher paramedic classes taught over three sites, and it extended the new employee orientation program from two to four weeks.

History of Community Paramedicine

In 1985, the Academy, which had operated out of space at Queens General Hospital for seven years, moved to its own larger facility at Fort Totten. With more space available, all training was consolidated there including new employee orientation, EMT and paramedic training and refreshers, supervisory classes, the emergency vehicle operating class, Haz Mat awareness, and many other programs.

In 1995, EMS instructors began training NYC Fire Department (FDNY) firefighters and company officers in the course titled Certified First Responder/Defibrillator. It was the first step in creating a true three-tiered EMS system. The following year, NYC*EMS was merged into FDNY and became the Bureau of Emergency Medical Services (BEMS).

By the mid-90s, EMTs and paramedics in the NYC EMS system were responding to 1.6 million emergency calls each year (over 4,000 calls per day). A significant increase in paramedic units was funded over the next decade, with some medics being additionally trained as rescue medics and equipped for hazardous materials, confined space and high angle rescue to enhance their collaboration with firefighters and NYPD emergency service officers on assignments. Following September 11 attacks, the BEMS received additional personal safety equipment, training and equipment to handle assignments in weapons of mass destruction, terrorism threats, and mass shootings. Since 1994, 24 ambulance stations have been added and over 4,200 BEMS EMT’s, paramedics and supervisors respond to emergency calls in the city.

A modern FDNY ambulance. (Photo/Kyle Barbaria)

In 2018, the BEMS paramedicine clinicians, along with the paramedicine clinicians employed by 13 voluntary hospital based ambulance agencies, together responded to 1,862,159 emergency medical calls:9 an average of 5,100 calls a day. During COVID, the call volume at times exceeded 7,000 calls per day.10,11

From the first call in 1869 to the most recent call in 2022, the men and women who dedicated themselves to work on these ambulances have responded to tens of millions of calls for help and have saved countless lives. This dedication has not been without cost; COVID and the 9/11 attack took terrible tolls on these personnel,12 and in 2022, the 147thambulance service provider died in service to the citizens of NYC.13

The system is also under great stress and the century and a half of history does not ensure its future. Today, largely due to a broken financial model, the EMS system across the U.S. has fallen far below the capabilities seen in other countries, paramedicine clinicians are terribly underpaid, their turnover rate is 25% a year, and they suffer the devastating consequences of extremely high rates of occupational fatalities and injuries.14-18

This paper documents over 150 years of emergency medical services by an uncountable number of personnel dedicated to saving lives and helping their patients through the worst moments of their lives. It highlights how individuals like Dr. Edward Dalton and Dr. Emily Dunning were able to change the course of history and create innovations that helped save countless lives. Over the past 50 years alone, the authors know a long list of individuals, and many small groups of thoughtful, committed citizens, who made tremendously positive transformations to the provision of EMS in NYC.

Today, thousands of dedicated paramedicine clinicians continue to provide the best possible care they can to all those who call for their help. We express our gratitude for their service, our honor for having been a part of this great effort, and our hope that the NYC EMS system, and the U.S. EMS system, will be able to flourish for the next 150 years.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense nor the U.S. Government.

Conflicts: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding: There was no funding for this project.

References

1. Staff. Roosevelt Hospital Ambulance Service – 1877 to 1972. Updated December 7, 2020. Available at: https://archives.icahn.mssm.edu/roosevelt-hospital-ambulance-service-1877-to-1972/. Accessed: November 7, 2022.

2. Knights E. Bellevue Hospital. History Magazine. Available at: http://www.history-magazine.com/bellevue.html. Accessed: 21 November 2022.

3. Staff. First Hospital Ambulance Service. Available at: https://essentialhospitals.org/about/history-of-public-hospitals-in-the-united-states/first-hospital-ambulance-service/. Accessed: November 7, 2022.

4. Museum of the City of New York. Available at: https://collections.mcny.org/CS.aspx?VP3=SearchResult&VBID=24UP1GMW1QCAR&SMLS=1&RW=1440&RH=758. Accessed: November 21, 2022.

5. Schroeder W. History of the ambulance service in Brooklyn, NY. Brooklyn Medical Journal. 1902; 16(9):381-395.

6. Staff. Biography: Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer. NLM: Changing the Face of Medicine. 2003. Available at: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_23.html. Accessed: November 11, 2022.

7. Staff. The History of Police Communications in New York City – Part 3 -Post WWII Two-Way Radio Communications. NYPD History. 2017. Available at: https://nypdhistory.com/communication3/. Accessed: November 11, 2022.

8. Savas E. Simulation and cost-effectiveness analysis of New York’s emergency ambulance service. Management science. 1969; 15(12):B-608-B-627.

9. New York City. Fire Department Statistics: Citywide Performance Indicators. 2019. Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/fdny/downloads/pdf/about/citywide-stat-2018-annual-report.pdf. Accessed: July 26, 2020.

10. Watkins A. N.Y.C.’s 911 System Is Overwhelmed. ‘I’m Terrified,’ a Paramedic Says. NY Times. March 28, 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/28/nyregion/nyc-coronavirus-ems.html. Accessed: July 26, 2020.

11. Pilgrim E, O’Brien K, Margolin J, Francis E. EMS on the front lines dealing with ‘madness,’ sleeping in their cars to avoid infecting their families. ABC News. March 31, 2020. Available at: https://abcnews.go.com/Health/ems-front-lines-dealing-madness-sleeping-cars-avoid/story?id=69901930. Accessed: July 26, 2020.

12. Maguire BJ, O’Neill BJ, Gerard DR, Maniscalco PM, Phelps S, Handal KA. Occupational fatalities among EMS clinicians and firefighters in the New York City Fire Department; January to August 2020. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. November 19, 2020. Available at: https://www.jems.com/2020/11/19/occupational-fatalities-among-ems-clinicians-and-firefighters/. Accessed: November 20, 2020.

13. Maguire BJ, Phelps S, O’Neill BJ. Work-Related Deaths Among New York City Ambulance Services Personnel: 1893-2022. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. November 10, 2022. Available at: https://www.jems.com/operations/work-related-deaths-nyc-ambulance-services-personnel-1893-2022/. Accessed: November 10, 2022.

14. Maguire BJ, Phelps S, Maniscalco PM, et al. Paramedicine Strategic Planning: Preparing the ‘far forward’ front lines for the second COVID-19 wave. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. May 14, 2020. Available at: https://www.jems.com/2020/05/14/paramedicine-strategic-planning/. Accessed: May 14, 2020.

15. AAA/Avesta. Ambulance Industry Employee Turnover Study. 2019. Available at: https://ambulance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/AAA-Avesta-2019-EMS-Employee-Turnover-Study-Final.pdf. Accessed: April 19, 2020.

16. Maguire BJ, Hunting KL, Smith GS, Levick NR. Occupational fatalities in emergency medical services: A hidden crisis. Ann Emerg Med. 2002; 40(6):625-632.

17. Maguire BJ, Hunting KL, Guidotti TL, Smith GS. Occupational injuries among emergency medical services personnel. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(4):405-411.

18. Maguire BJ, Smith S. Injuries and fatalities among emergency medical technicians and paramedics in the United States. Prehosp and Disaster Med. 2013; 28(4):1-7.